Christ Higham. ‘The Great Divide’.

One of the passages from today’s first reading, Jeremiah 17: 9, first came to my attention when I was about 25 years old and it recurs to me fairly often. ‘More tortuous than all else is the human heart, beyond remedy; who can understand it?’ Now the first half of the passage is variously translated, depending upon which Bible you use, and a brief perusal of some of the possibilities can be interesting: ‘The heart is deceitful above all things and beyond cure.’ ‘The heart is deceitful above all things, and desperately corrupt.’ ‘The heart is deceitful above all things, and desperately wicked.’ ‘The heart is deceitful above all things, and incurable in wickedness.’ ‘The heart is perverse above all things and unsearchable.’ These are just some of the ways translators have attempted to render the Hebrew, Greek, Latin or other text they were working from. Applying these attempts to our own experience of life can, and should be, quite an absorbing experience.

Part of the sense I get from all this is that the human heart is complex in the extreme. It is many-sided and full of twists and turns. This in itself need not be bad: God made us in his own image, after all, and our souls are to created to reflect in some sense the tremendous depths and beautiful heights of God himself. But we are fallen, too, because of sin, and one of the important things Lent calls us to reflect upon is the perverseness and deceitfulness of our own hearts, not only in how we relate to God, but also in how we relate to others and even to ourselves. How many of us have the courage really to do that?

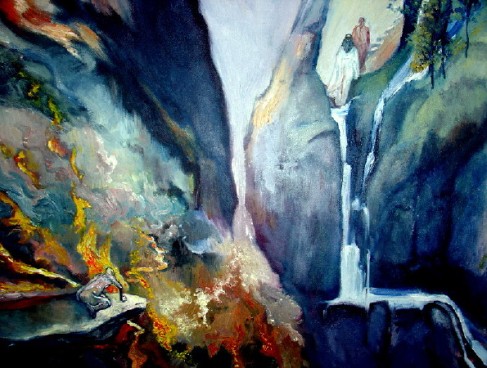

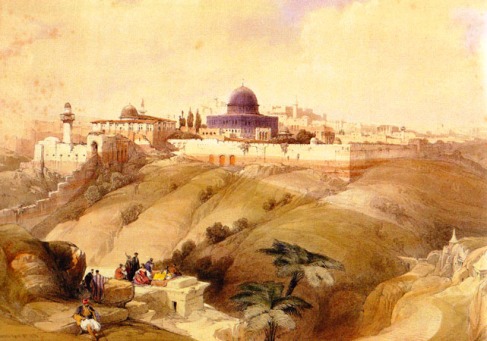

Here is a fine quote from St. Isaac the Syrian, the 7th century mystic, which I think can provide a useful meditation for those who want to contemplate both the passage from Isaiah above and today’s Gospel reading from Luke concerning the rich man and Lazarus: ‘As for me, I would say that those being tormented in hell are done so by the blows of love. What is there more bitter and violent than love’s torments? Those who feel they have sinned against love bear a far greater condemnation in themselves than the most dreadful of punishments. The suffering that our sins against love put in the heart rends it far more than any other torment….By its very power love acts in two ways. It torment sinners just as, here below, it can happen that a friend torments a friend. And it gives joy in itself to those who have observed what should be done. This, according to my understanding, is what the torment of hell is: regret. But the souls of those above are intoxicated with delight.’ (from Discourses, 1st Series, no. 84)

You must be logged in to post a comment.