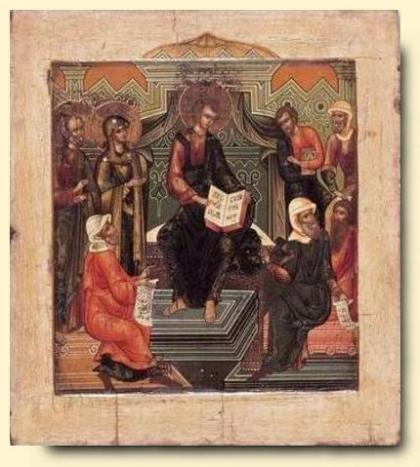

Holy Resurrection of the Lord. Contemporary Georgian Icon. Egg tempera on board.

The second reading for today’s Easter mass is Colossians 3: 1-4, and it also forms the very short reading which comes at the very end of the liturgical hour of Prime during the entire Paschal season, as one last brief but profound meditation before beginning the other activities of the day: ‘If then you were raised with Christ, seek what is above, where Christ is seated at the right hand of God. Think of what is above, not of what is on earth. For you have died, and your life is hidden with Christ in God. When Christ your life appears, then you will appear with him in glory.’

I first started thinking more about this passage a couple of years ago and find that it recurs to me periodically, usually when I’m out for a walk, when I least expect it. It constitutes a real challenge to us who are otherwise immersed in all manner of daily pleasures, troubles and concerns, and, spiritually speaking, this is really a dangerous state of affairs. As Pope Francis I said just yesterday at the Easter Vigil in Rome: ‘Our daily problems and worries can wrap us up in ourselves, in sadness and bitterness, and that is where death is.’ So, no matter what we are doing, if we can pause for a moment and try to raise our hearts and minds to God, to the heavenly realm of saints and angels to which we are called, and which lies literally a mere heartbeat away, then we can begin to put into practice what St. Paul exhorts the Colossians to do in today’s reading.

Often we can get a new insight into a scriptural passage by looking at a different translation. In this regard, I think the Latin Vulgate text can be really helpful. Where the English says ‘Think of what is above,’ the Vulgate says ‘quae sursum sunt sapite’, and ‘sapite’ has a whole range of meanings, from ‘think’ to ‘taste’ to ‘discern’ to ‘have a taste for’ to ‘be wise as a result of discerning.’ May we all not only think of what is in heaven, then, but taste, discern, develop a taste for, and learn from discerning the life to which we are called as members of the Church, the Mystical Body of Christ. May we see its hope and consolation shining brightly through whatever darkness dims our days.

‘This is the day the Lord has made; let us rejoice and be glad in it.’ Now a very fine meditation on this response to the psalm sung in today’s liturgy comes from Blessed John Henry Newman: ‘We have had enough of weariness, and dreariness, and listlessness, and sorrow, and remorse. We have had enough of this troublesome world. We have had enough of its noise and din. Noise is its best music. But now there is stillness; and it is a stillness that speaks…such is our blessedness now. Calm and serene days have begun; and Christ is heard in them, and his “still small voice”, because the world speaks not. Let us only put off the world, and we put on Christ…May that unclothing be unto us a clothing upon of things invisible and imperishable! May we grow in grace, and in the knowledge of our Lord and Savior, season after season, year after year, till he takes us to himself…into the kingdom of his Father and our Father, his God and our God.’ (From the sermon ‘The Difficulty of Realizing Sacred Privileges.’)

You must be logged in to post a comment.