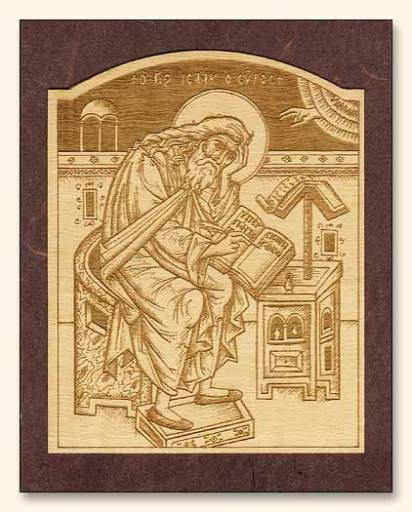

Manuscript page from ‘The Meditations of St. Anselm.’ Illumination on parchment by an unknown 12th century miniaturist. Bodleian Library.

On this Fourth Sunday of Easter we also commemorate St. Anselm (1033-1109), an Italian- born Archbishop of Canterbury perhaps best known for his definition of theology as ‘fides quaerens intellectum’ (‘faith seeking understanding’). And this feast day happily falls on a Sunday when our Gospel is John 10: 27-30, in which Jesus says ‘My sheep hear my voice; I know them, and they follow me.’ Because it was a central feature of St. Anselm’s spiritual and intellectual endeavor to explore how God knows and loves man, and how man comes to know and love God. Though St. Anselm is counted among the so-called ‘scholastic’ theologians, who are sometimes criticized for the ‘overlogicalness’ of their approach, it is important to remember that, for St. Anselm at least, it all began with faith. ‘Nor do I seek to understand that I may believe,’ he wrote, perhaps echoing a thought earlier expressed by St. Augustine, ‘but I believe that I may understand. For this, too, I believe, that, unless I first believe, I shall not understand.’ How different all this seems from the world today, in which not only is St. Anselm’s approach generally reversed at best, but more often both halves of it are rejected unconsidered. We might do well to turn to St. Anselm’s own homily ‘On Faith in the Trinity’, still read on this day in some Benedictine monastic communities. Here are some excerpts, which I believe can help us to approach today’s Gospel with deeper appreciation.

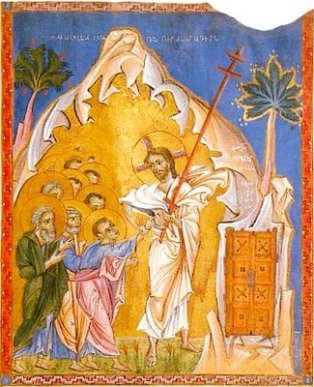

‘Holy Writ urges us to seek out doctrine, saying: “Unless you believe, you cannot understand,” thus openly admonishing us to bend our minds toward understanding, since we are shown the means of attainment. I also believe that between faith and the fulness of understanding there is a middle state: I think a certain amount of that understanding which we all so eagerly desire comes to us in proportion to the intensity with which we seek it. From this consideration, therefore, although I am a man of so little wisdom, I do sometimes rise to contemplation in accordance with the measure of divine grace that has been granted to me.’ It is true that, whether we are participating in the Eucharistic liturgy, studying Holy Scripture, meditating upon the writings of our Fathers in the faith, or attending to the various prayers of the Church, we should do so with the devout expectation that we will sanctified by these sources of God’s own self-revelation to man; we will be drawn into the divine life of God; we will be brought, according to our inner disposition and the mercies of God’s grace, into deeper understandings of the truths and realities of faith, which will not be forced upon us, and which are granted only to those who seek and desire them with faith. Then we can hear the Shepherd’s voice. Then we can follow him.

For St. Anselm, a vital precondition for coming to know and love God had to do with how we live our lives. ‘We must first cleanse our hearts by faith,’ he says in this same homily, ‘for the Scriptures say: “Purifying your hearts by faith.” And we must first enlighten our eyes by keeping the commandments of God, for: “The commandment of the Lord is pure, and gives light unto the eyes.” And we must first become as babes in humble obedience to the testimony of God, if we are to speak of wisdom…We must first, I say, if we wish to penetrate into the depths of things spiritual, put away all that pertains to the flesh, and must live according to the spirit.’ In this St. Anselm reminds me of no one so much as St. Nectarios of Aegina (1846-1920), who said that ‘Christianity is a religion of revelation. The Divine reveals its glory only to those who have been perfected through virtue.’ Now a life centered upon the virtues (actions which are true, just, chaste, kindly, honest, etc., and the dispositions which underly them), would seem to some to be simply the end product of faith and understanding. But it works the other way around too: the more we seek to live out the virtues and to love them, the deeper our faith and understanding of things divinely revealed grows. As St. Gregory the Great said of the Good Shepherd in a homily on today’s Gospel passage: ‘Those who love me are willing to follow me, for anyone who does not love the truth has not yet come to know.’

You must be logged in to post a comment.