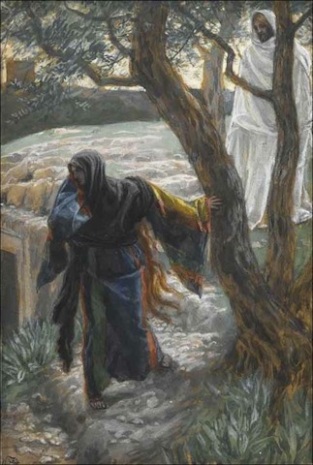

James Jacques Tissot. ‘Christ Appears on the Shore of the Sea of Tiberias.’ Between 1884-1896. Watercolor over graphite on paper. Brooklyn Museum, New York.

There are several very curious elements to today’s Gospel reading (John 21: 1-14) in which the Risen Lord appears to some of his principal disciples who are fishing at the Sea of Tiberias. Why have they gone fishing immediately after the crucifixion and Resurrection? Why do they not recognize Jesus when he appears? Why do they catch nothing, but then bring in a massive haul of fish at the Lord’s direction? Why does the naked Simon Peter gird himself and leap into the sea when he realizes that Jesus is there? Why does the Lord offer them bread and roasted fish on shore? The careful reader will note even more intriguing things in the passage than these, but here we have a start.

The terrified and distraught disciples may simply have wanted to withdraw from Jerusalem and the by turns horrific (crucifixion) and joyous (Resurrection) scenes they had just witnessed. To use a perhaps poor analogy from our own lives, we often enjoy returning to ordinary domestic activities to settle our minds after returning from participation in some especially tragic or even extremely happy event. In the early Church, the disciples’ failure to recognize Jesus was often ascribed to their hardness of heart, dullness of mind and lack of faith, and I believe that patristic reading could well be applied here. St. Peter Chrysologus, a 5th century bishop of Ravenna, believed that it was the ‘beloved disciple’ John who was the first to recognize the Lord because ‘Love brings a sharper focus to bear on everything and the one who loves always feels with more intensity.’ St. Peter Chrysologus also wrote that Peter girded himself before leaping into the sea because ‘The guilty always cover themselves to conceal themselves. Thus, like Adam, Peter wanted to hide his nakedness today after his wrongdoing; both of them, before sinning, were clothed only by a holy nakedness. He hoped that the sea would wash the dirty clothes representing his betrayal. He jumped into the sea because he wanted to be the first to return, he to whom the greatest responsibilities had been entrusted. He girded his tunic around him because he was to gird himself for a martyr’s combat, according to the Lord’s words: “Another will gird you and lead you where you would rather not go.”‘ (John 21: 18)

The eating of roasted fish and bread on shore is of course reminiscent of the multiplication miracles found elsewhere in the Gospels, symbols of God’s power and providence. But the early Christians saw a special significance in the roasted fish, which they thought symbolized Christ himself, who had suffered and offered himself as a victim reminiscent of the ‘burnt offerings’ of the Old Testament. They even had a Latin saying: ‘Piscis assus, Christus passus” (‘The fish burnt, the Christ suffered’). The failure of the disciples to catch anything before the arrival of the Risen Lord may symbolize their powerlessness to proclaim the Gospel or convert people to Christ without faith and without Christ himself. St. Peter Chrysologous indeed saw the great catch of fish obtained at the Lord’s direction to contain a lesson about the conversion of souls to the life of the Church: ‘With great difficulty they bring back with them the Church cast to the winds of the world. This is what these men bring along to the light of heaven in the net of the Gospel and snatch from the deep to lead to the Lord.’ [I have taken these quotations from Sermon 78 by St. Peter Chrysologus, which you can find in various English translations online or in print.]